Kinney Azalea Gardens: Rhode Island’s Hidden Gem

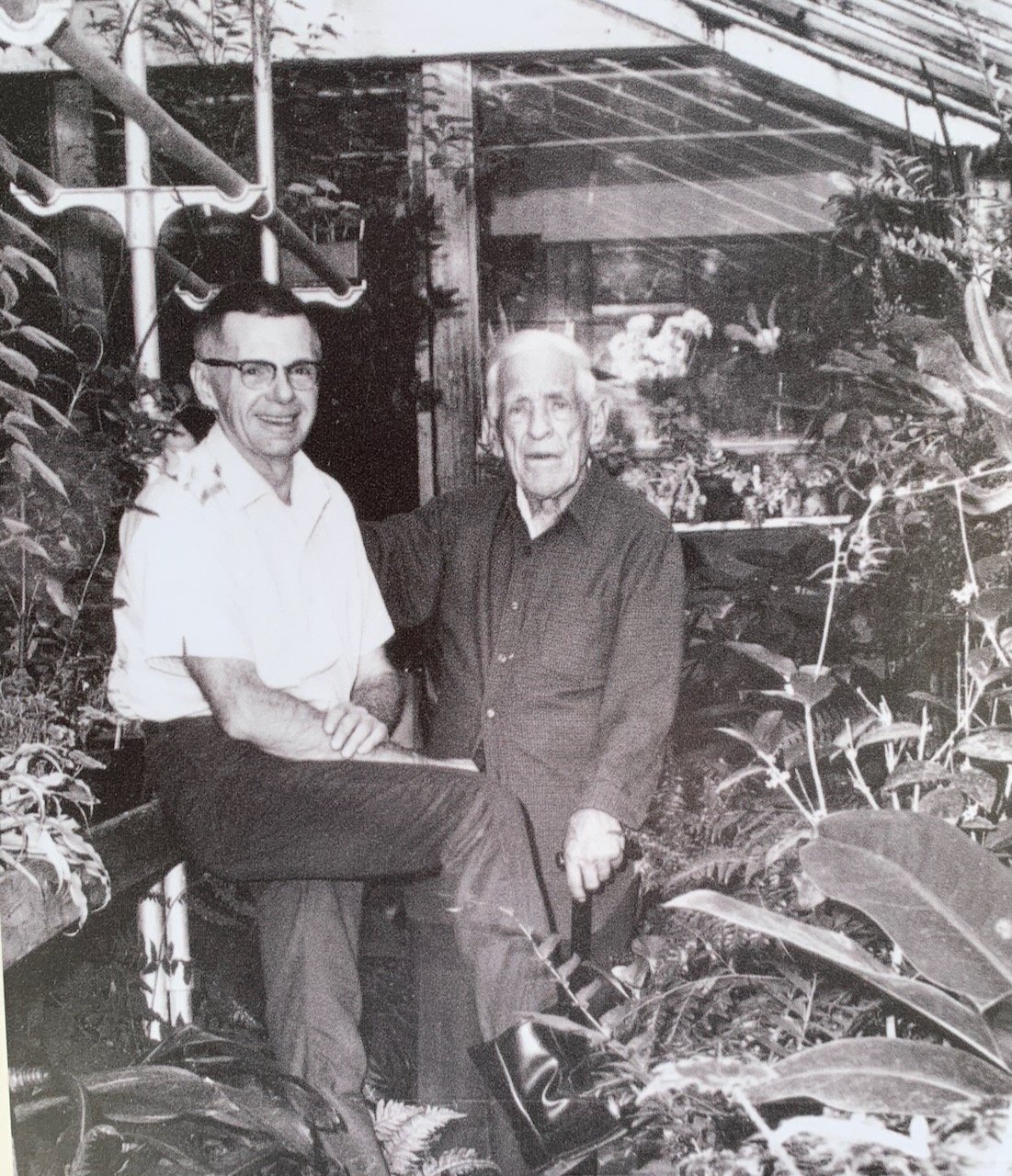

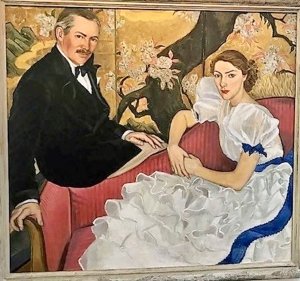

/The Kinney Azalea Gardens are a hidden gem—a private garden that grew out of the horticultural passions of Lorenzo Kinney, Jr, who moved there with his wife, Elizabeth, in 1927. The first azalea and rhododendron plants were planted shortly, with help from Lorenzo’s father, the first professor of botany at the nearby University of Rhode Island. Lorenzo inherited a love of horticulture from his father, and a love of plein air oil painting from his mother, who was URI’s first painting professor. Lorenzo was able to pursue both in the creation of his garden.

Azaleas became his passion after visiting Elizabeth’s native Virginia and seeing the extensive azalea plantings in southern estates. At that time, there were few azaleas available for northern gardens, so Lorenzo began collecting azaleas from the southern U.S. and from around the world, and hybridizing his own—a hobby that turned into a second career. His hybrids, known as the K-series, can be seen on the K Path in the garden. A beautiful peach hybrid is named in honor of Elizabeth.

With help from many high school and college students, Lorenzo planted five acres of gardens. One of those high school students, Susan Gordon, went on to earn a doctorate in plant sciences. She worked extensively with Lorenzo from 1976 until his death in 1994 at the age of 100. The gardens have stayed in the Kinney family, and visitors are still welcomed!

Dr. Gordon manages the gardens and continues to develop new hybrids. She has planted a sixth acre as Galle’s Footsteps, a series of five footprints, each devoted to an azalea hybridizer. The area is dedicated to the late Fred Galle, author, horticulturist and friend of Lorenzo’s. She has also created naturalized areas with native shrubs and perennials to preserve the biodiversity of the garden.

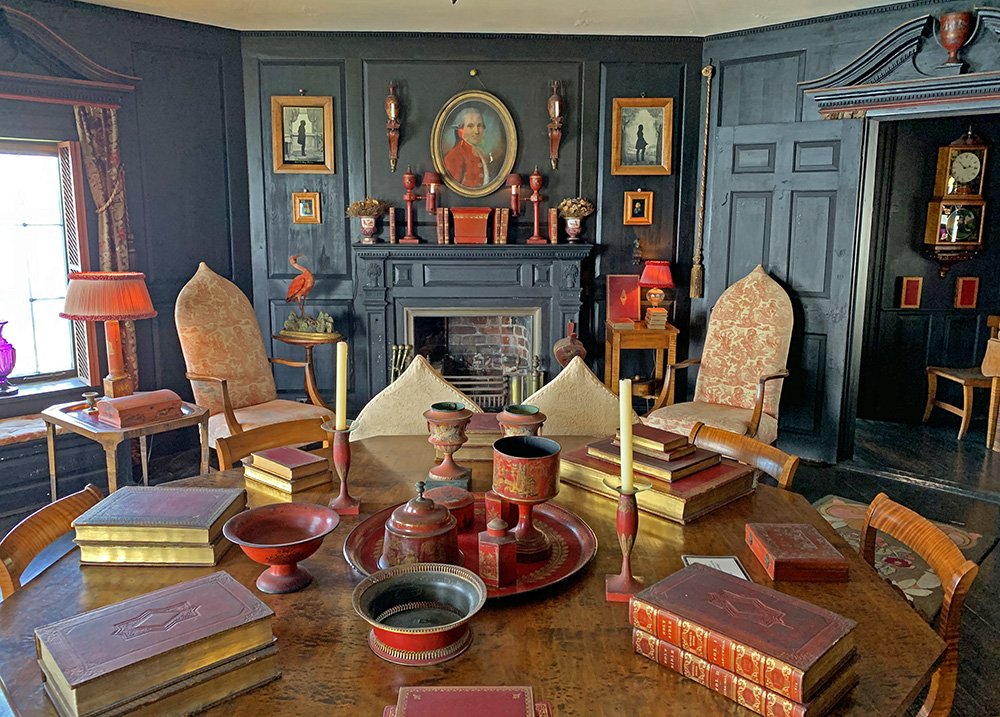

The azaleas are at their peak from mid-May to early June, when the garden is ablaze in pink, white, red and coral. There are hundreds of azalea and rhododendron cultivars, and collections of mountain laurel, boxwood, pieris, leucothoe, itea, calycanthus, and oakleaf hydrangeas. You will also find a stand of mature umbrella pines that was a wedding gift to Lorenzo from his parents, and a 10-foot circular moongate that was built by a local landscape architect and stonemason.

You can also purchase azaleas, rhododendrons, leucothoe, mountain laurel, and other shrubs, both in pots and as full-grown specimens from the garden. Cash and check only.

Kinney Azalea Gardens, 2391 Kingstown Rd. (Rte 108), South Kingstown, RI 02879, (401) 782-8847, kinneyazaleagardens.com. Admission by donation, open daily dawn to dusk, street parking.

You Might Also Like