The Elms: A Luxurious Newport Mansion Garden

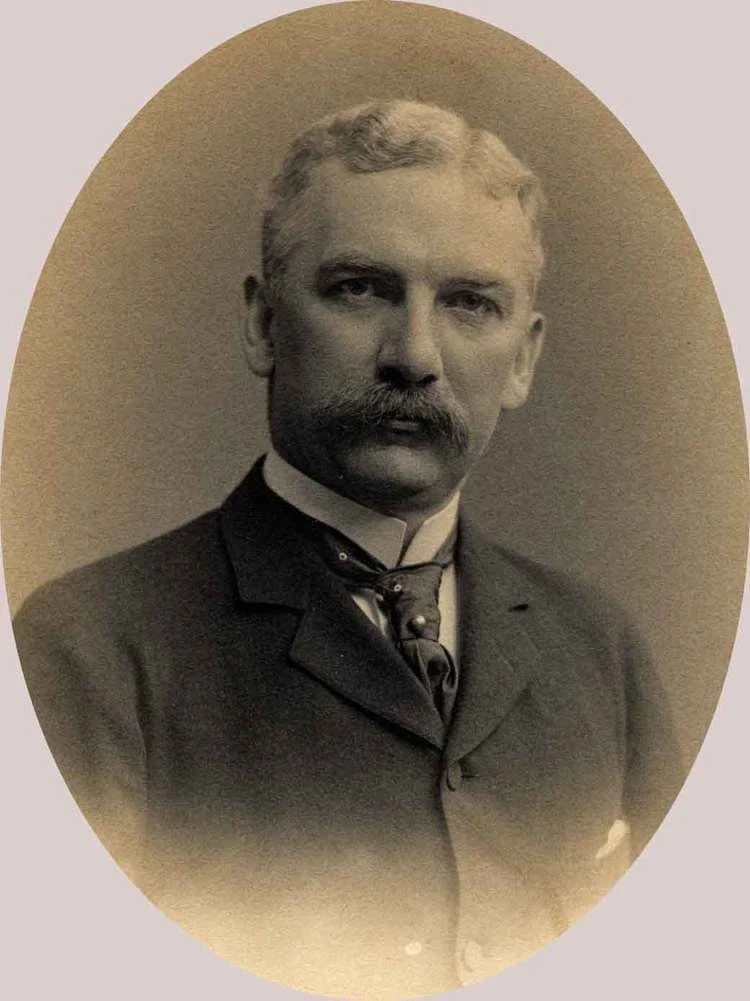

/The Elms is one of the grandest mansions in Newport. Fans of The Gilded Age serial have seen the servant kitchens and one of its bedrooms appear as parts of the Russell residence. One of the finest examples of Beaux Arts architecture and landscape in America, The Elms was built by Edward Julius and Herminie Berwind of Philadelphia and New York. Edward was the son of a German immigrant and made his fortune in the coal industry. He was considered one of the 30 most powerful men in the United States, and counted President Teddy Roosevelt and Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany among his personal friends. Herminie’s father was a junior partner at the largest American marble works, served as the American Consul to Florence, Italy, and was an accomplished sculptor. Together, the Berwinds shared a passion for music, the arts, and entertaining.

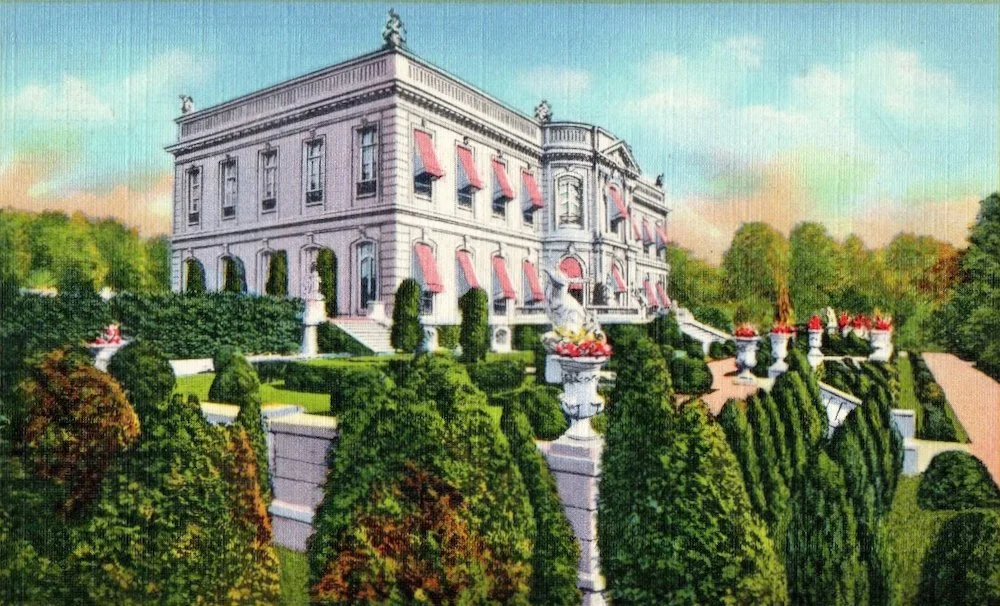

They hired Philadelphia architect Horace Trumbauer to design a summer estate modeled after the mid-18th-century French chateau d’Asnieres. Construction of The Elms was completed in 1901 at a reported cost of $1.4 million.

The gardens of The Elms were developed from 1902 to 1914 under the direction of Trumbauer, who produced the drawings and plans for the grand allée, marble pavilions, and sunken garden. The gardens were originally conceived as a place for staging grand entertainments and as an outdoor sculpture gallery, with several large pieces by European sculptors.

The Elms is a prime example of the Classical Revival Style in architecture and landscape design. During the late 1880s, both patrons and architects were attracted to French classicism as a new approach for estates with formal, aristocratic pretensions. Newport had become the most fashionable summer resort, and therefore the logical site for the American version of the maison de plaisance, or pleasure pavilion, a French concept that idealized a perfect unification of house and garden. At The Elms, the terraces ease the transition from the ballroom to the open air. They also provide a platform from which viewers could observe the garden.

From 1902 to 1907, the gardens were a picturesque park with specimen trees and a small lily pond. After 1907, the garden underwent changes due to newer theories in American landscape architecture. In the early 20th century, tastes in America became heavily influenced by Charles Adams Platt and Edith Wharton, both of whom published works exhorting Italian villas and their gardens.

Stylish Americans adapted their country estates by adding gravel-lined forecourts, planted terracing, formal stairs and water features, herbaceous borders, and pergolas. Trumbauer reworked The Elms’ garden to reflect this new revival of classical Italian design. The pond became the present sunken garden at the back of the estate. Viewed from the terraces and summerhouses, the intricate patterning of annuals, ivy, yews, and euonymous is delightful.

The Great Lawn, planted with specimen trees, connected the house to the new gardens. Immense weeping beeches partially concealed the fountains and pavilions, creating a sense of intrigue. An allee of topiaries was installed parallel to the sunken garden. A new garage, stable, and carriage house complex was designed to appear as a French chateau with its own terrace, arcade, fountain, and topiaries.

The Berwinds did not have any children. After his wife's death, Edward enlisted his sister, Julia, to act as the hostess at his homes in Newport and New York City. Edward died in 1936, and Julia enjoyed spending summers at The Elms until her death in 1961. Since none of the relatives were interested in the property, the family auctioned off the contents of the estate and sold the property to a developer. In 1962, just weeks before it was to be demolished, The Elms was purchased by the Preservation Society of Newport County for $116,000 and opened as a museum.

The Elms is a wonderful destination at all times of the year. The mansion is beautifully decorated for Christmas every year, and a new cafe in the carriage house offers lunch both indoors and on the patio.

The Elms, 367 Bellevue Ave., Newport, RI (401) 847-1000, newportmansions.org/explore/the-elms