Rotch-Jones-Duff House & Garden Museum

/Rotch-Jones-Duff House & Garden Museum is a wonderful place to visit from June to September, when the exquisite rose garden is in bloom.

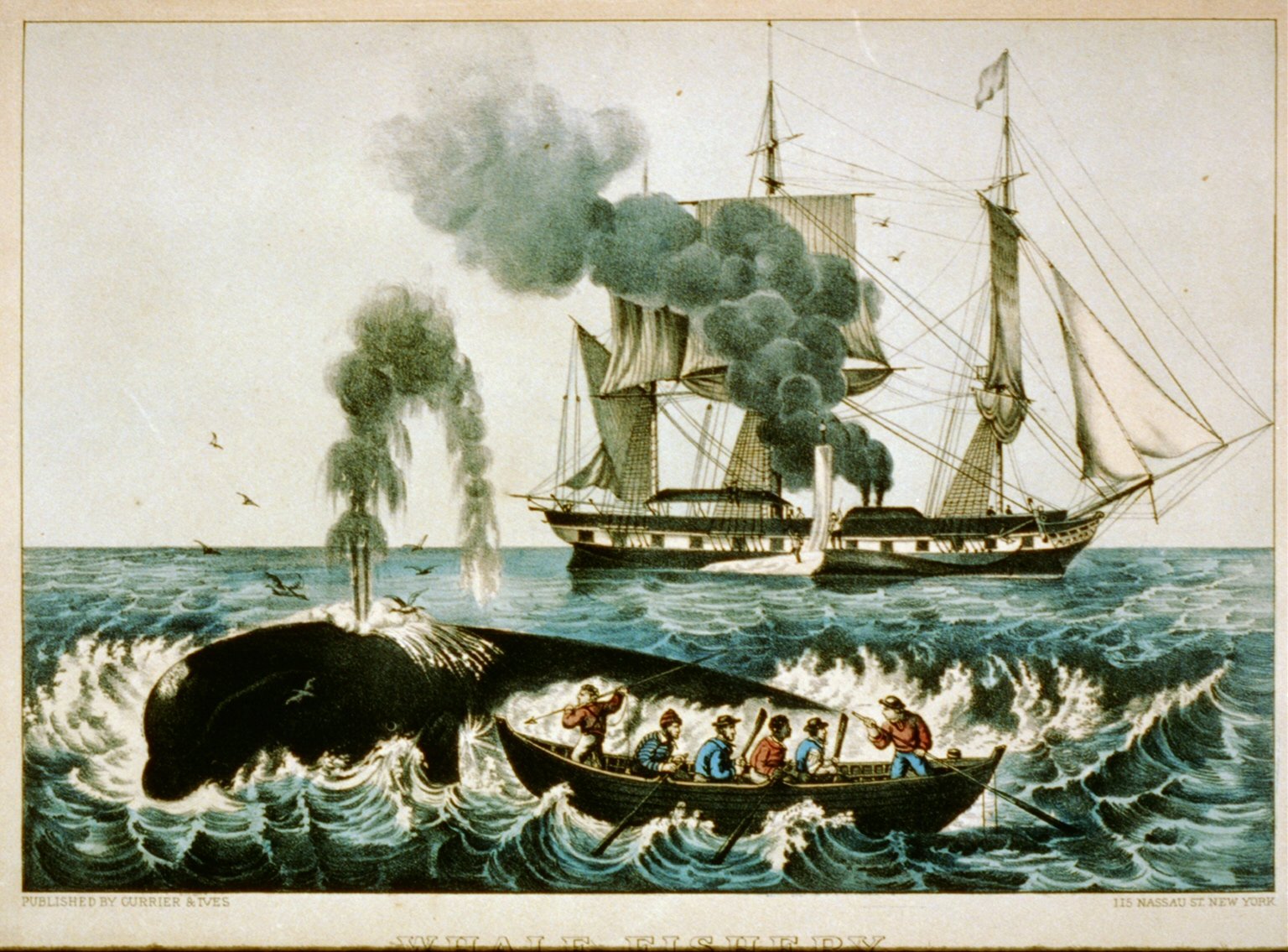

The three families whose names were given to the Rotch-Jones-Duff House all shared close ties to New Bedford’s dominance of the whaling industry in the 19th century. The beautiful Greek Revival mansion was built in 1834 for William Rotch Jr., one of the wealthiest and most influential citizens of New Bedford. Rotch was a Quaker who had distinguished himself by helping to found several banks and schools. He built his house on a hill overlooking the port, with room for expansive gardens on the south-facing side of the property. Rotch had a tremendous passion for horticulture, with a particular interest in the cultivation of pears, which were a popular fruit in New Bedford at that time. He created a bountiful garden of vegetables, fruits, and exotic ornamental species brought back from whaling voyages. Rotch founded the New Bedford Horticultural Society. He shared his horticultural interests with his son-in-law James Arnold who would later become benefactor of the Arnold Arboretum. (Below: William Rotch, Jr and James Arnold and family)

Edward Coffin Jones, a successful whaling agent, purchased the mansion in 1851. The Jones family expanded the garden and added the Victorian pergola situated at the main axis of the ornamental gardens. Jones’s daughter Amelia Hickling Jones lived in the house for 85 years. Photographs of the garden from the late 19th century show the pergola covered with wisteria and parterre beds edged with boxwood and filled with roses, hollyhocks, and calla lilies. Amelia became a prominent philanthropist in the community supporting the arts and founding a children’s hospital. With no heirs, the property was offered for sale when she died in 1935.

photo courtesy of rotch-jones-duff house

In 1936 the property was purchased by successful businessman and politician Mark M. Duff whose fortune was made in whale oil, coal, and oil transportation. Duff hired Mrs. John Coolidge, a Boston landscape architect, to enhance the garden with ornamental beds, reflecting pools, and graceful walkways. Duff was extremely fond of tulips, and more than 7,000 bulbs were planted during the Duff tenure, which concluded in 1981.

Today elements of all three residencies remain. A massive copper beech, planted by Amelia Jones in the 1880s, greets you at the front entrance of the mansion. On the left side of the house, stone steps descend to the formal boxwood rose parterre garden, the star of the property. The best view is from the porch of the house, where you can clearly see the pattern. The 19th-century wooden lattice pergola punctuates the garden, and its intricate lattice work casts lovely shadow patterns on the ground below. An heirloom apple orchard is sited nearby.

The Garden Club of Buzzards Bay has been involved in restoring these and other gardens on the property since 1982. In the southeast corner, the club has created the kind of naturalistic woodland garden that might have existed on the site in the late 19th and early 20th centuries while referencing modern horticultural and environmental practices. Here you will find trilliums, Tiarella, trout lilies, and Solomon’s seal in early spring. The club also operates the historic greenhouse and maintains an adjacent historic collection of about 50 boxwood specimens.

Rotch-Jones-Duff House & Garden Museum, 396 County St., New Bedford, MA 02740

508-997-1401, rjdmuseum.org

Hours: May–Oct.: Wed.–Sat. 10–4, Sun. 12–4.

You Might Also Like