Gilded Age Garden on the Connecticut Shore

/During my recent Long Island’s Splendor trip, we stopped at this historic mansion and gardens. With gorgeous views of Long Island Sound, Harkness Memorial State Park is a beautifully landscaped recreation area along the Connecticut shoreline. It was the private summer home of the Harkness family during the Gilded Age, and boasts elegant gardens designed by Beatrix Farrand.

The focal point of the park is Eolia, a 42-room Roman Renaissance-style mansion built in 1906, and purchased by Edward and Mary Harkness in 1907. It was named Eolia for the island home of Aeolus, keeper of the winds in Greek mythology. The Harknesses acquired their fortune through substantial investments in John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company, and like many of the wealthy class during this period, they spent summers in the countryside.

Eolia was one of seven Harkness residences and the family’s summer retreat. The 230-acre property was a working farm with poultry, dairy cows, a vegetable garden, and an orchard. The grounds included a nine-hole golf course and a windmill that pumped water into the home’s 20,000-gallon water tank.

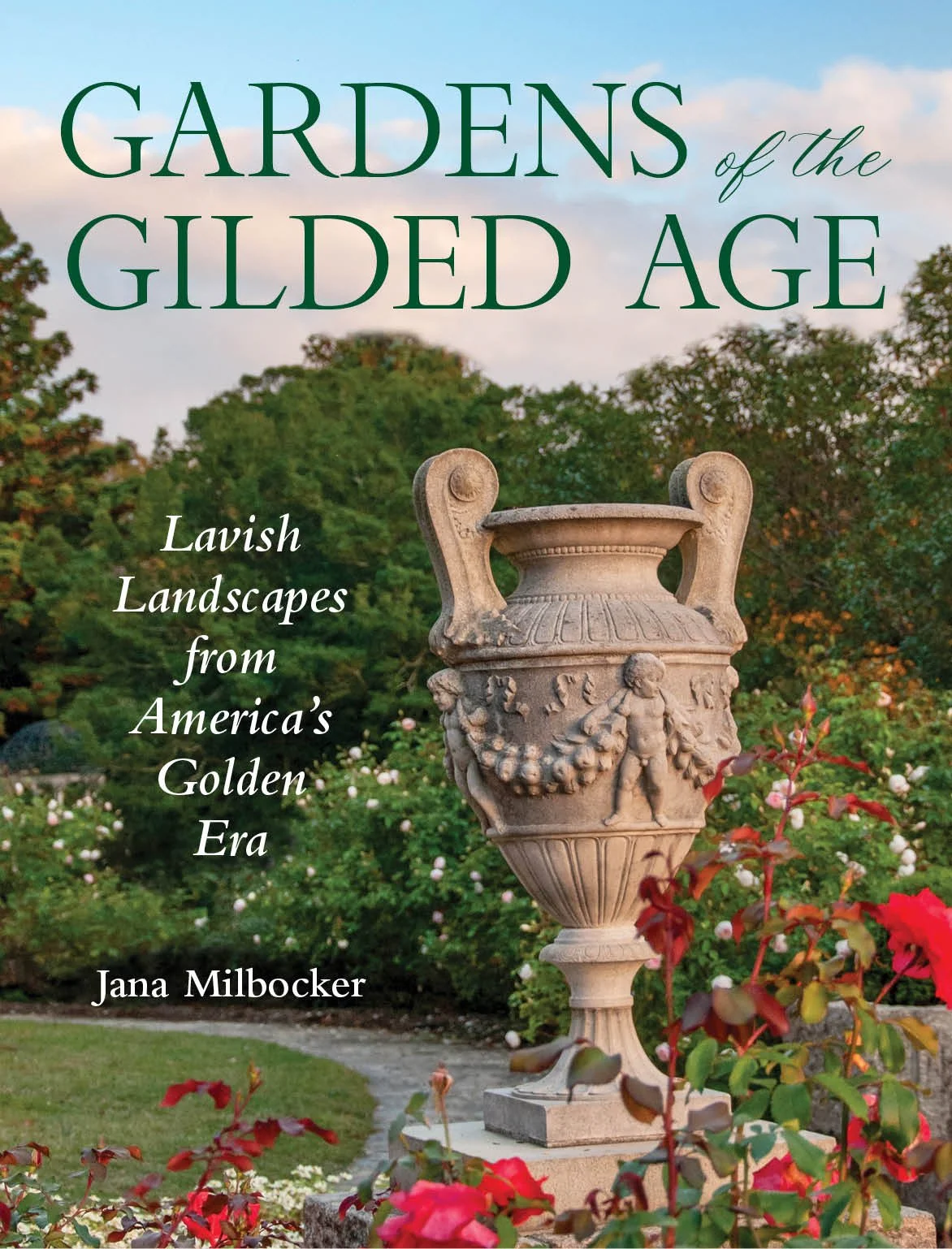

James Gamble Rogers created a grand walled garden with classical sculpture, an elevated wisteria-clad pergola overlooking Long Island Sound, tennis courts, and a lawn extending from a formal fountain court.

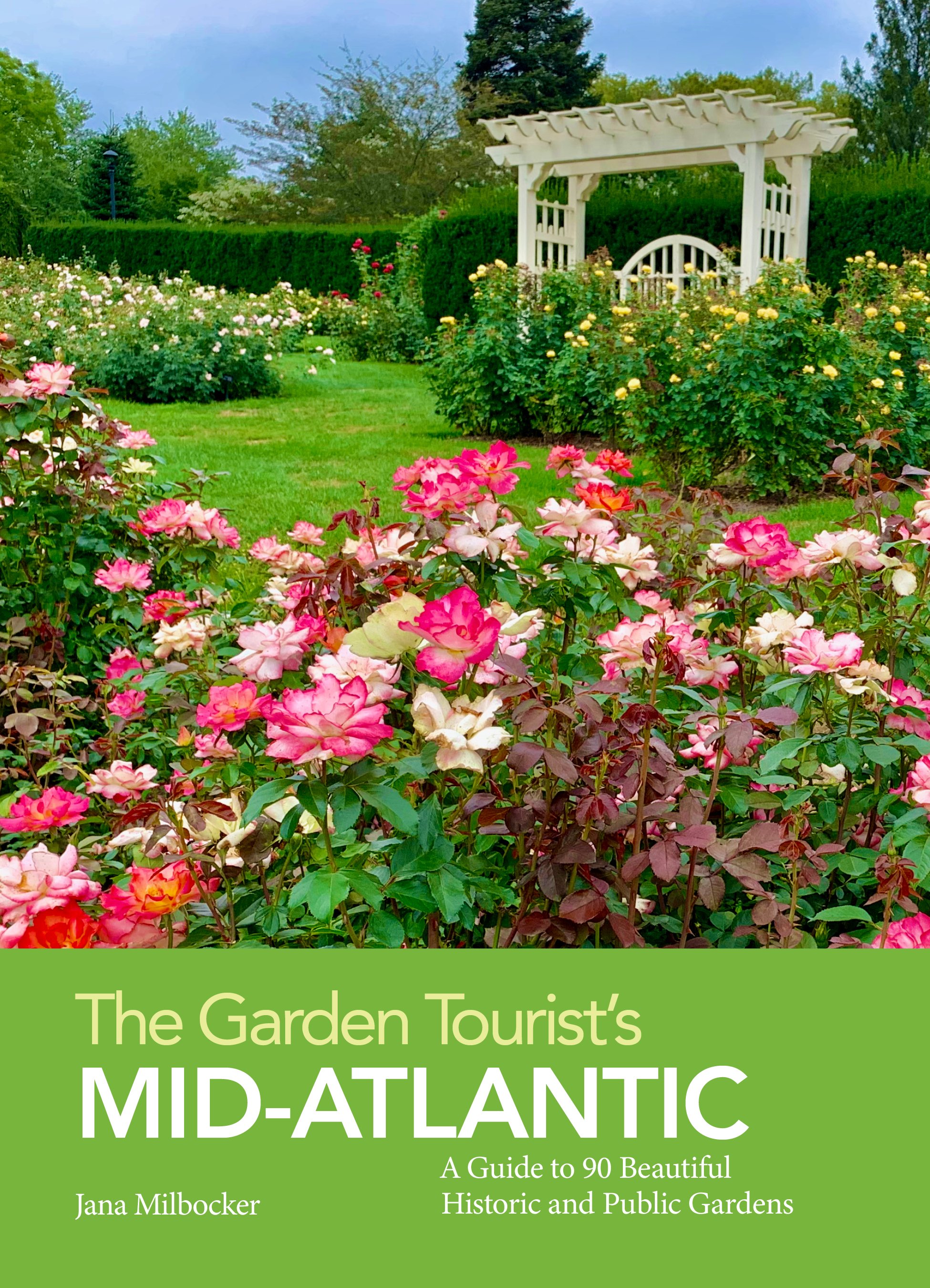

In 1919 Beatrix Farrand remodeled the gardens. She converted the tennis court into the Oriental Garden—a special setting for the family’s collection of Chinese and Korean vases and sculpture. Formal in layout, the garden featured a sunken grass panel and a central reflecting pool, and was planted with billowing flowers in soft pastels—baby’s breath, dianthus, roses, lavender, and lilies—punctuated with heliotrope standards.

Farrand revised the West Garden to a more naturalistic planting scheme, added a boxwood parterre surrounded by a whimsical wrought iron fence, and planted a sloping rock garden with alpine plants. Upon Farrand’s retirement from practice in 1949, Marian Coffin updated the plantings in the East Garden. The gardens were faithfully restored to Farrand’s and Coffin’s plans by the Friends of Harkness in the 1990s.

The property includes the original farmhouse and servants’ quarters, as well as the remains of the windmill and the Lord & Burnham greenhouse that once provided seedlings for the Harkness gardens and later for the State Capitol and other park facilities. Mature specimen trees and the remains of a cutting garden provide a glimpse of the property’s bygone days. A stroll along the Niering Walk, a grass trail that winds through a native marsh, leads to Goshen Cove. A footpath from the imposing back lawn leads right down to the sandy beach.

Upon her death in 1950, Mary Harkness left the property to the State of Connecticut “for health purposes,” with a third designated as a summer camp for handicapped groups and the remainder as a state park.

Harkness Memorial State Park, 275 Great Neck Rd., Waterford, CT 06385, ct.gov/deep, friendsofharkness.org

You Might Also Like: