Spring Ideas from Blithewold

/Joan and I had the pleasure of presenting our lecture "Spring Ephemerals and Other Delights" at Blithewold last April. For those of you that have never been there, Blithewold is a 33-acre estate with a 45-room mansion framed by a series of lovely gardens overlooking Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island. The property was purchased in 1895 by Augustus and Bessie Van Wickle, and served as the family summer home. The gardens were designed in the late 1800s, and feature a 10-acre lawn, an arboretum of specimen trees, perennials gardens, and a "bouquet" or scenic woodland. Bessie and her daughter Marjorie were ardent gardeners and turned the estate into a horticultural showplace.

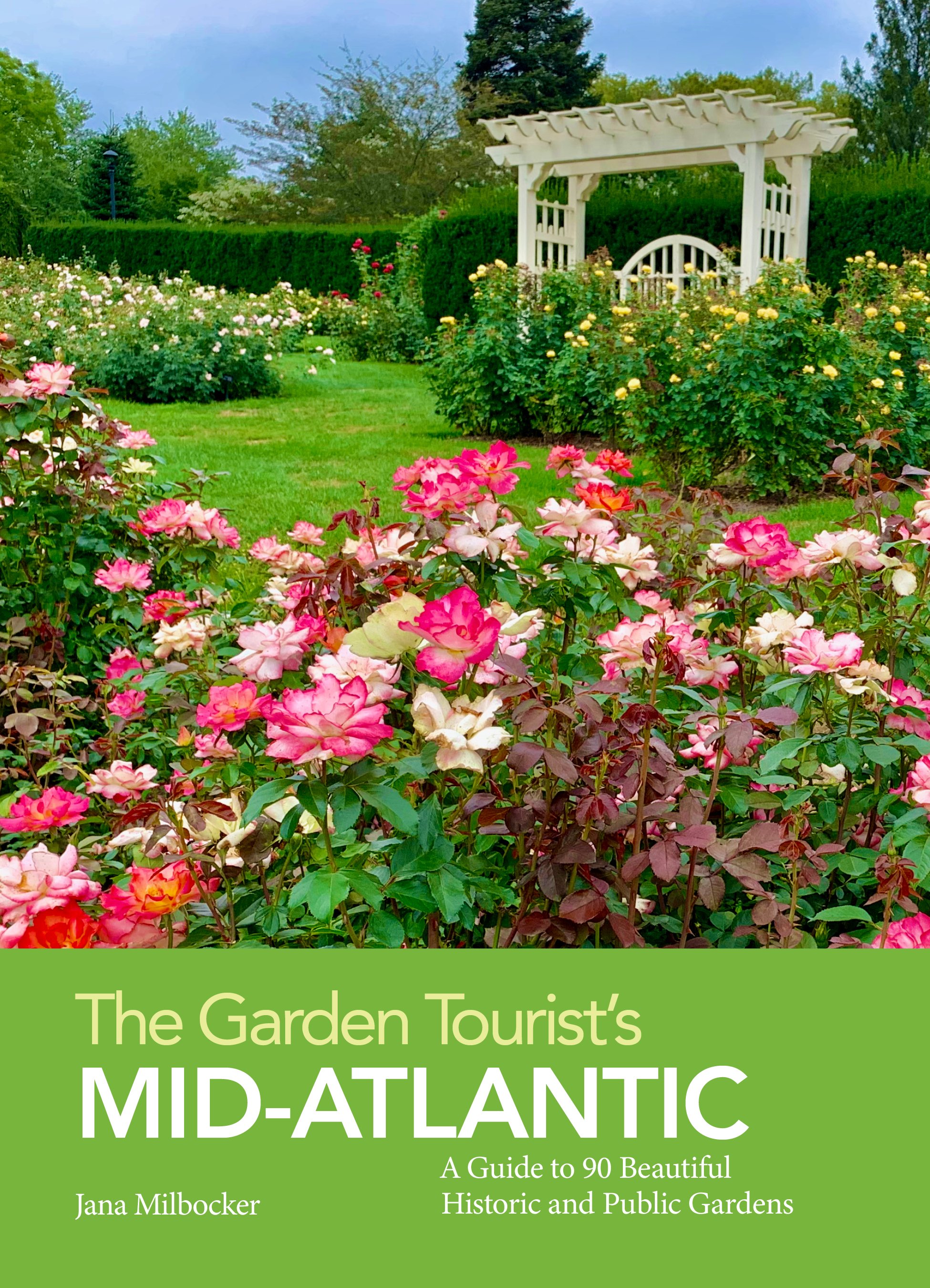

Blithewold is beautiful in all seasons. In the spring, the rose garden, framed by an Asian-inspired moon gate, blooms with colorful bulbs and early perennials.

Tulips, leucojum, grape hyacinths, bleeding hearts, euphorbia and other perennials welcome you to the Blithewold estate.

Century-old trees present a sculptural beauty even in early spring, before they leaf out. Some are underplanted with shade and drought-tolerant perennials such as epimedium (below).

The chartreuse leaves of ginkgo trees are a delight when viewed against the mature deep green conifers.

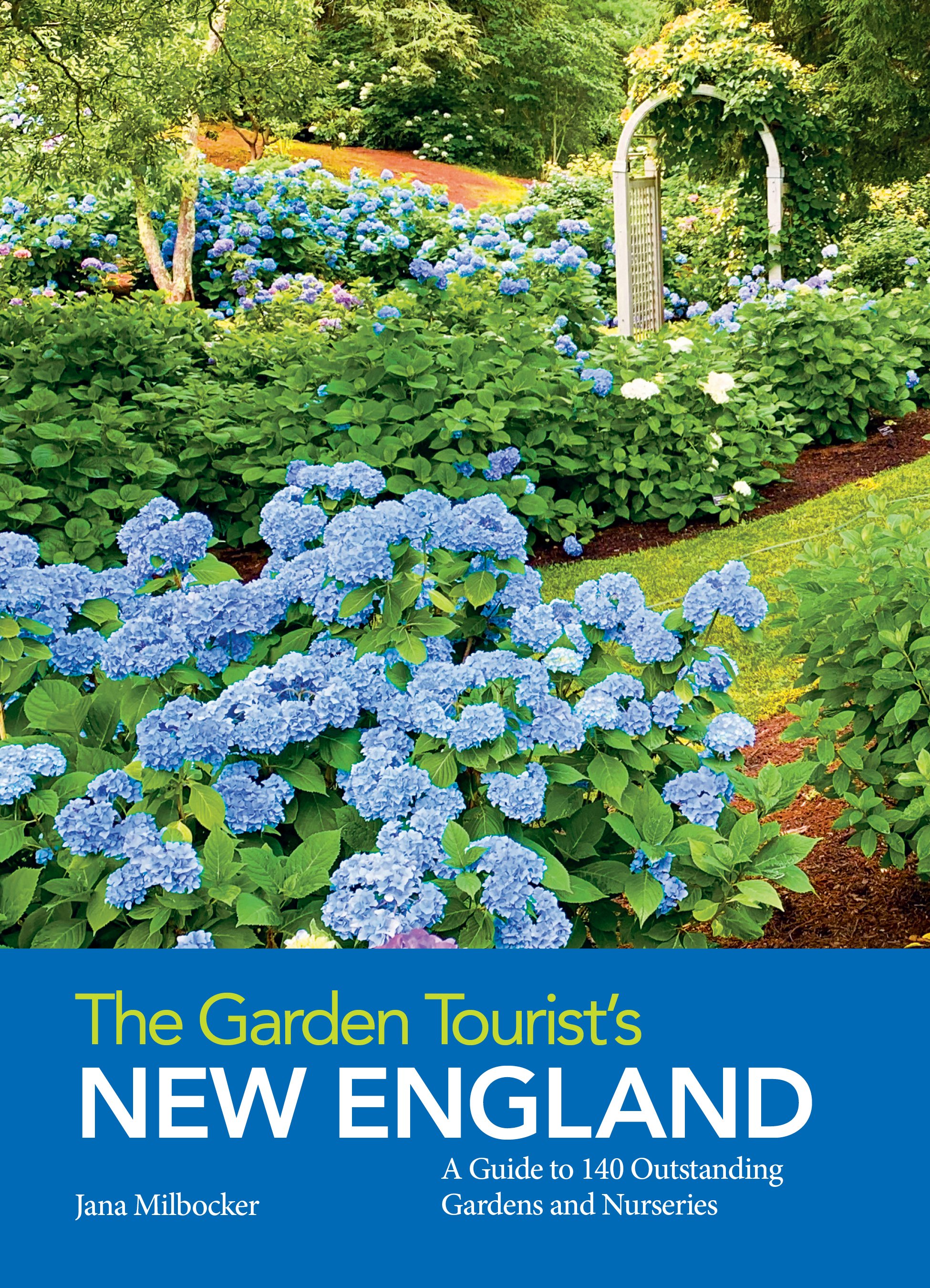

The Bosque is planted with thousands of daffodils and a carpet of spring ephemerals including mayapples (above) and erythronium, also known as trout lilies (below). These woodland plants bloom while there is ample sunlight before the trees leaf out, and become dormant in the summer.

The Van Wickles used stone from their property to create rock gardens and garden ornaments such as the whimsical stone bench below.

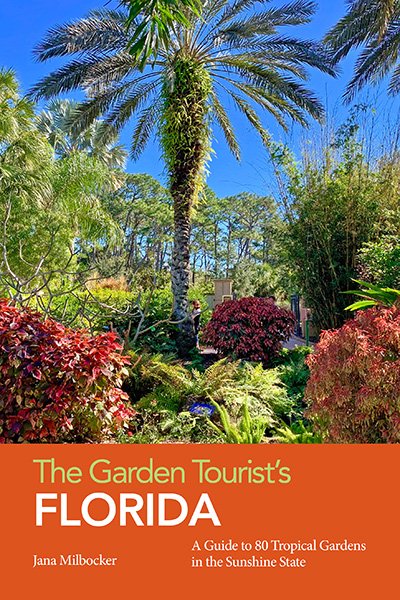

Flowering crabapples frame the view of Narragansett Bay. In April, you can view more than 50,000 daffodils in bloom. In May, see the Magnolias, Flowering Cherries, Honeysuckles, Weigelas, Lilacs, and Viburnum, along with hundreds of blooming perennials.

Joan and I will be back at Blithewold on Monday, May 8 at 1:00 pm, presenting our "Propagating Perennials" workshop. Hope you can join us!